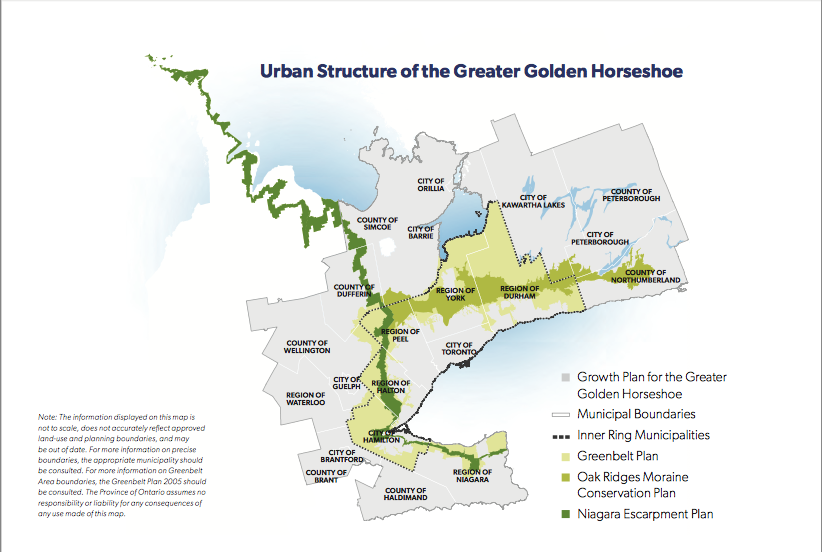

Greenbelt Plan Map, 2022 (ontario.ca)

When the Ontario Auditor General’s Special Report on Changes to the Greenbelt was released on August 9th, 2023, the impact was felt across the Toronto region. I study greenbelts (I have written several articles and a book chapter, and was on the Ontario Greenbelt Council for 10 years) but never had I witnessed so many people discussing the Greenbelt and what it means to them. On one hand, the Greenbelt Foundation consistently finds that nine out of ten people in Ontario support the Greenbelt, so I shouldn’t have been surprised that neighbours and friends were interested in talking to me about the fate of the Greenbelt. The call in show on CBC Ontario Today (August 10, 2023) was jam-packed with callers interested in discussing the politics of conservation and planning with The Narwhal reporter Fatima Syed, who is covering the issue.

The Auditor General’s report is absolutely damning to the current government, finding the actions of the Premier highly objectionable, bordering perhaps on racketeering. The pressure did not let up as the media through editorials and follow-up articles continued to ask questions of the government.

The Greenbelt lands in the end were not removed by the Premier and the Greenbelt Plan is today perhaps stronger than ever (Bill 136 passed December 6, 2023). Phew!

My remaining concern is that urban planning, although represented well in the Auditor General’s report (she includes a solid history of the Greenbelt and description of the planning process), was not really visible in the discussions that people have come forward with. The changes to the Greenbelt were a deliberate attack on the planning process, which was (and still is in many ways) overridden.

Planning is not very visible to most people, even though the process to plan, approve, and build just about anything takes a lot of time and effort. As a planner, I offer the following thoughts arising from the Greenbelt debacle from a planning perspective.

Planning is a black box to most people. Understandably (as with many types of professions), most people don’t realize extensive processes is going on behind the scenes until they see the impact of those processes. In the case of planning, the impact of planning processes that people see is land being cleared and building construction starting. So many considerations go into deciding where and when lands should be developed, to make sure that we still have natural processes to support life in and around cities (clean water, stormwater management, clean air, wildlife in some sort of balance), and to make sure that when people move in to their houses or apartments the infrastructure to support their lives is largely in place. The “red tape” of the planning process is to ensure that there will be roads, sidewalks, parks, clean water flowing from taps, electricity hooked up so the lights go on, and to make sure the sewers are working, waste will be picked up, and more.

North Oakville shown as the Town of Oakville’s new urban area. Note the green Greenbelt lands in the northwest corner (oakville.ca)

In many new communities, the process takes years. In Oakville, the new urban area of North Oakville from the start of planning to new construction took 20 years, I studied the plans as they emerged for this new urban area north of Dundas Street in Oakville (and a bit in Burlington). The regional study that identified North Oakville as the next growth area began in the early 1990s (maybe even earlier? I worked on the Halton Urban Structure Plan completed in 1994). The land use plans were approved in the late 2000s. The first time I saw homes being built was in 2011. Is the process too long? Maybe. Certainly as planners we should be working in a timely manner to make sure that we are focusing on doing the studies, coordinating work, and negotiating plans.

In southern Ontario, if you own a property and you wish to use it for something else, you go through a process that is set out. If approved, you get in a queue according to the phasing of infrastructure as this must precede building. Planning for water and wastewater infrastructure is an enormous task; building that infrastructure is also huge in terms of money and labour. My understanding is that there are many homes in the queue in southern Ontario already, just waiting for infrastructure, as detailed in the Regional Planning Commissioners report by Hemson. The process may be imperfect, but generally fair, as all property owners and developers generally go through the same steps.

Ford in the Greenbelt fiasco attempted to upend the process. He knowingly and deliberately tried to help a handful of developers to jump the queue. We have a process (a putatively first-come, first-served line for approvals) where it’s deliberately difficult to go to your local politician and make a deal. Ford actions are the kind of racketeering that the entire process is meant to suppress. His actions—in addition to the Greenbelt land removal attempt—include: his Minister’s Zoning Orders (MZOs), his clawing back the environmental oversight of the Conservation Authorities, his decision to get rid of regional municipalities (going against all best planning principles about the need for municipalities to cooperate about service provision beyond their own boundaries; and noting that the Regional Planning Commissioners were the ones that the Auditor General went to for info on the 1.5 million homes!), and getting rid of the Growth Plan (the plan that set very high intensification targets and created a more measured urban boundary expansion process to prevent sprawl).

I’m especially concerned about the Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) for those working in the Ministry of Municipal Affairs (p. 33 of the report). Is there anything that screams “not ethical” more than an NDA (NDAs are meant, I think, to cover up the effects of entitled people behaving badly). Regarding the NDAs, I have great discomfort because I am concerned about the difficulties that must have been faced by the province’s planners (especially if any are Registered Professional Planners), who have an ethical responsibility to act in the public interest.

Ford almost wept in the news conference on August 9th about the housing needs of new Canadians, but what about access to nature? local food? climate change impacts? People want to come to Ontario because of the quality of life. Without conserving the lands that support our health, everyone’s quality of life will be diminished (see Syed’s article on the same). How can we ask people to live in high-rise buildings if we do not offer them public spaces and natural areas to visit? Nothing tells the tale more about the need to have more areas for natural heritage conservation and recreation than the overloaded Greenbelt trails and conservation areas in the summer and fall, where many public areas now require reservations.

Ford has succeeded in doing the opposite of the actions needed to build new housing and communities as he has set the planning process topsy-turvy. He instead could invest directly in infrastructure needed to fast-track water servicing for approved areas (as the Regional Planning Commissioners concluded).

He could fixe the planning process by creative means. He could work with planners to create better local negotiation processes for development approvals (less combative, more collaborative, more mediation). Today, city councillors (and interest groups) can delay smaller infill and intensification developments, which discourages smaller “missing middle” housing. No wonder we only have a few big developers (a colleague of mine called them an “oligopoly”) as it’s so difficult to be so financially leveraged over so many years waiting to get anything built.

Planning cities and the regions around them is not easy. Waving a magic wand and changing the designation of lands from “protected” to “next in line for development” through nepotism is surely a planning crime. Balancing diverse opinions about what should be built in a place and how is not easy. There’s no doubt room for improvement, even so. The havoc created over the past few years has made the process worse, not better.

For students interested in environment and planning, I would suggest reading Michael Hough’s Cities and Natural Process (1995) I keep assigning it in class even though it is becoming quite dated because students seem to get a lot from it. He captures the sense of working with the landscape that has so influenced my interest in landscape and planning (he was one of my FES major paper supervisors).

For students interested in environment and planning, I would suggest reading Michael Hough’s Cities and Natural Process (1995) I keep assigning it in class even though it is becoming quite dated because students seem to get a lot from it. He captures the sense of working with the landscape that has so influenced my interest in landscape and planning (he was one of my FES major paper supervisors). I thoroughly enjoy reading Witold Rybczynski’s A Clearing in the Distance (2000) about the life and work of Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the first landscape architects. The book is a good read, especially the bit about the making of Central Park in Manhattan.

I thoroughly enjoy reading Witold Rybczynski’s A Clearing in the Distance (2000) about the life and work of Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the first landscape architects. The book is a good read, especially the bit about the making of Central Park in Manhattan. Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia (2009) is a great introduction to the making of North American suburbs. I especially like Hayden’s focus on landscape and settlement patterns created by the myriad of choices people make about their everyday lives.

Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia (2009) is a great introduction to the making of North American suburbs. I especially like Hayden’s focus on landscape and settlement patterns created by the myriad of choices people make about their everyday lives.